|

Alexandra do Carmo Page 1 | 2 | Biography | Information & News |

|||||||||

|

|||||||||

|

meanings and messages are fractured, making the reading richer through that which is called “poetic licence” semiotics. The hypertext drawn out in Office/Commercial would thus come close to a puzzle with the perceptive appearance of a zapping process, in which what is suggested is much more efficient than what is suggested by a thing, if we follow Borges.

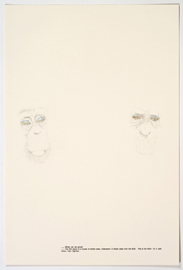

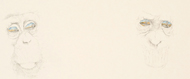

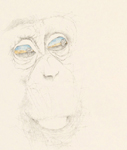

The figure of the chimpanzee, which in this case takes on a tormented appearance, with blurred edges in which the imperceptible stands out, stands as evasion and disorientation in its distorted gesture, but also as a process; as a process of the construction of a language. I am thinking of how Samuel Beckett, in an article on Proust, points out our inclination towards the vulnerable and sensitive when we are taken out of the safe context of our daily surroundings. Alexandra do Carmo seems to wish something to emphasise something like this in many of her projects, aware |

|

|||||||

|

blurred edges in which the imperceptible stands out, stands as evasion and disorientation in its distorted gesture, but also as a process; as a process of the construction of a language. I am thinking of how Samuel Beckett, in an article on Proust, points out our inclination towards the vulnerable and sensitive when we are taken out of the safe context of our daily surroundings. Alexandra do Carmo seems to wish something to emphasise something like this in many of her projects, aware of the cryptic sense of contemporary art for a non-specialised spectator, overwhelmed by doubt and attracted by that impossibility that emanates from the indiscernible and alien that it may produce, but above all obliged to make an effort, like the chimpanzee, to reach an interpretation that he ends up being unable to reach. To see, or to understand? To look at, or to read? To observe, or to interpret? How many questions might we ask ourselves about the possible reading or non-reading that the figure of the chimpanzee might take from the images? And if we, the public, are the chimpanzee, and the project is what we call art, what do we understand about that art that virtually flow from those images projected by the chimpanzee?The question posed by Alexandra do Carmo is merely that of how to communicate from the position of the artist and whether that communication is truly possible.

|

|||||||||

|

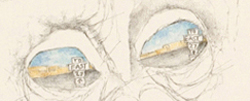

The masked used for this search – that of the chimpanzee – may be insignificant, although in this case it is not. The chimpanzee, which is very close to the human being in its genetic make-up, is a key towards emphasising the fiction that the very act of drawing already contains within itself. Also to reveal the artist’s gaze, and, of course, a sense of humour contained in each one of these portraits-self-portraits. The fictionalised reality functions as a mirror in the eyes of that chimpanzee that ends up granting expression to a drawing that is apparently similar but which always bears the tones and marks of previous attempts and mistakes. In Alexandra do Carmo’s drawings one may read notes capable of remaining there, in the same drawing, from much before the result we see.

|

|

a mirror in the eyes of that chimpanzee that ends up granting expression to a drawing that is apparently similar but which always bears the tones and marks of previous attempts and mistakes. In Alexandra do Carmo’s drawings one may read notes capable of remaining there, in the same drawing, from much before the result we see. While the spectator reads these notes he is, unwillingly, caught in the image-reflection of the chimpanzee’s eyes, as if he were involved in that same space, as the main character of the tale by Salvador Elizondo, La historia según Pao Cheng, felt:On a summer’s day the philosopher Pao Cheng sat down on the bank of a stream to foretell his destiny in a shell of a turtle. Before the eyes of his imagination, great nations fell and small ones were born which later became great and powerful before falling in their turn. The force of his imagination was such that he felt himself walking through its streets. Through one of the windows, he could make out a man writing. Pao Cheng then looked at the sheets of paper lying on an edge of

|

|||||||

|

|||||||||

SIGN UP FOR NEWSLETTERS

SERVICE OVERVIEW

SIGN UP for ARTIST MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for GALLERY MEMBERSHIP

NEWSLETTERS & ANNOUNCEMENTS

NEWSLETTER SCHEDULE

ARTIST OPPORTUNITIES

POST ARTIST OPPORTUNITY

SERVICE OVERVIEW

SIGN UP for ARTIST MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for GALLERY MEMBERSHIP

NEWSLETTERS & ANNOUNCEMENTS

NEWSLETTER SCHEDULE

ARTIST OPPORTUNITIES

POST ARTIST OPPORTUNITY

Click on the map to search the directory