|

Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne: WANG XINGWEI - 13 Apr 2012 to 7 July 2012 Current Exhibition |

||||

|

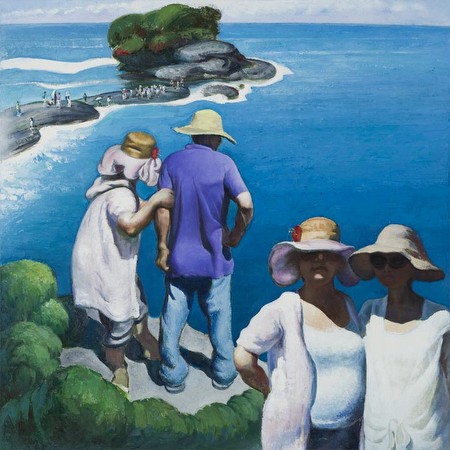

Wang Xingwei, "Pura Tanah Lot Temple" 2011

oil on canvas, 150 x 150 cm Courtesy: Galerie Urs Meile, Beijing-Lucerne |

|||

|

||||

|

WANG XINGWEI Opening: Friday, 13 April 2012, 6 – 8 pm Exhibition: 13 April – 7 July 2012 Wang Xingwei (*1969 in Shengyang, China; works and lives in Beijing) does not come from an artistic family. It was a natural-born love of painting, rather than his background, that led him to become an artist. The end of 1980s marked the official start of his career as a painter. Since the mid-1990s, his artistic practice, which is rich in subtle cultural and historical references, has been defined by the concurrency of diverse conceptual, stylistic and formal experimentations. Wang Xingwei is no longer the artistic youth that was known for wearing hand-knitted woollen trousers. He has constructed an exquisitely unique and picturesque language of seemingly disconnected elements - conceptual entries from his own “visual dictionary”. These elements are juxtaposed in order to purposely dismantle the acknowledged logic of thinking and create, by means of their disruptive power, new and unpredictable interpretative possibilities. The exhibition will show a collection of approximatley 12 of Wang Xingwei’s paintings from 2009 up until the present day. The exhibition has been divided into two parts - Indoor Views and Outdoor Views. The latter will present audiences with “Big Tree by the Film Museum No. 2“ (2011), a traditional life study. This is a rare opportunity to view such works, given the artist’s usual approach of working from readymade images. The Indoor Views space will investigate the continuous evolution and progression of the artist’s “Old Lady“ series, which consists of a number of very similar works. As the curator Zhang Li said: “They present a lively, complex art form, the one we call ‘painting’.” An informal talk between Nataline Colonnello and Wang Xingwei on the occasion of the exhibition “Wang Xingwei” at Galerie Urs Meile in Beijing Venue: Galerie Urs Meile Beijing-Lucerne, Beijing Time: 3.30PM, Saturday 15 October 2011 Nataline Colonnello: After more than two years of preparation, you eventually resolved to entitle this conceptually and stylistically multilayered solo-exhibition with your own name. What were your reasons? Wang Xingwei: The name of my last exhibition was “Wang Xingwei – one-man show”, and the title of this new show is “Wang Xingwei”. The majority of the works in this show are called untitled and the content provided in brackets after their names is mainly for purposes of identification. I have found it very difficult to find a specific word to accurately describe my current state. Maybe my name is the most appropriate one. I am not saying that my name has some kind of special meaning, but that it is the most appropriate representative of my current state and feelings. NC: The paintings in the exhibition are divided into two main themes – “Indoor Views” and “Outdoor Views”. Was this your intention when painting these works? WXW: I wasn’t thinking of that while I was painting. I only thought of the two themes when I was discussing the installation of the exhibition. Dividing the works into two sections according to either indoor or outdoor characteristics is probably the most common and most fundamental method of classification. NC: In a number of your recent paintings, some of characters from your earlier works have suddenly reappeared, after many years, in different contexts and with different functions. For example, the subject of untitled (painter) (2011), is reminiscent of the man in The Night in Shanghai (2004); and the woman in Female Body and Geometric Solid (2011), is a figure you previously portrayed in Regret (2001). The new exhibition also shows a number of totally new characters that reoccur and metamorphose throughout different canvases, which you have created in a limited period of time. In the “old ladies” series, the subject has become a symbol that, in combination with other images, has undergone a process of systematic deconstruction, fusion and restructuring. It is as if it has become a kind of metaphor, or a kind or satirical and critical perspective on the contemporary art education system in China. WXW: The metaphorical and critical aspects that you just mentioned are actually only of secondary value. I am focused on how to maximize the value of form. By forming the image of the old lady again and again I have squeezed out the maximum possibilities of this form, a little like a capitalist wringing out the maximum surplus value from the masses. The core issue of oil painting or even painting in general is how to give form a conceptual and logical foundation. Everything else is of secondary value – I ignore anything else, it is not the focus of my approach. NC: In the many different images of old ladies, we can not only see a revolutionary transformation of shape and meaning, but also a detailed study of form, composition and the relationship between human figures and the background. In untitled (flowerpot old lady) (2011), a flowerpot is substituted for the old lady’s head, becoming part of the human body. Do you think we can also find this kind of “displacement” in the “Outdoor Views” section? WXW: These works are all very closely connected. One reason is that I completed them all during the same period of time - some images stay around. In other words, they take time to fade away. It’s just like when we look at things, and sometimes the image stays in our eyes for a while after it has actually disappeared. Sometimes the scene disappears but some of the images within the scene remain. For example, the flowerpot that you mentioned was caused by my subjective visual awareness. The old lady’s head that has changed into a vegetable is actually a variation of the works Big Tree by the Film Museum (2010) and Big Tree by the Film Museum No. 2 (2011). When I painted those trees, I felt that they had a kind of human element in their form, so the head of the old lady also comes entirely from the image of the flowerpot. It is true that there are connections between the works. This shift is not significantly related to the “Indoor” and “Outdoor” categories, but is related to the serial nature and continuity of the works. For example, in the Comrade Xiao He series, (2008), Xiao He’s right hand evolves into a goose’s head in later versions. NC: Can you tell me more about the importance of the transformation of shape and proportion from a technical standpoint? For example, in Female Body and Geometric Solid , the simplification and juxtaposition of the volumetric elements are instrumental to the creation of a kind of new logic and relations on a psychological level. WXW: I agree. Actually, this was constructed upon my own hypothesis – I imagined that all of the images on the canvases were internally related, and as they became closer the connections between them become increasingly strong. External connections are relations of volume. I simplify and strengthen volumetric relations in order to attain simple and strong external relationships. The aim of strengthening volume is not only to “see” and “know”, but moreover to “enter” and “experience”. You will penetrate and become the volume, so it will often produce a psychological effect. NC: In the works that are shown in this exhibition you have presented three images of a painter: the female painter that appears in untitled (Chinese brush No. 2) (2010), who is “popular in the Western market”; the “actor” that appears in The Night in Shanghai and untitled (painter) (2011); and the portrait of Mao Yan, a real painter. Why have you painted so many painters? WXW: Actually Mao Yan is also one of my “actors”, because the background of the painting is originally from a scene of a movie. I am very interested in the role of the painter, because I find it very difficult to paint a self-portrait now. So I am very interested in other people holding brushes. NC: In terms of the source materials of your works, some are entirely fictional, such as the painter holding the brush, some are new renderings of other people’s works, such as Harmonious Smiles (2011), and some are based on real people, such as the famous TV anchorman Bai Yansong in Bai Yansong (2011). How do you see the relationship between reality and imagination? WXW: This question leads us back to the issue of “squeezing”, which we talked about before. In fact I always work with the aim of squeezing out value from form – this is my original starting point. Both fictional images and forms from reality are a starting point for me. They are all objects waiting for me to explore them; in fact all images are like this. Of course, other secondary values of these images also have important meanings and uses. I understand this fully and I don’t deny it, but these other values were not my original point of approach. In fact all paintings are the same; nothing is meaningless. |

||||

|

||||

re-title.com

International contemporary art

SIGN UP FOR NEWSLETTERS

SIGN UP for ARTIST MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for GALLERY MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for ARTIST MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for GALLERY MEMBERSHIP

Click on the map to search the directory