|

Golden Thread Gallery: Lisa Malone - Metronome Art Projects @ London Art Fair - 14 Jan 2010 to 30 Jan 2010 Current Exhibition |

||||

|

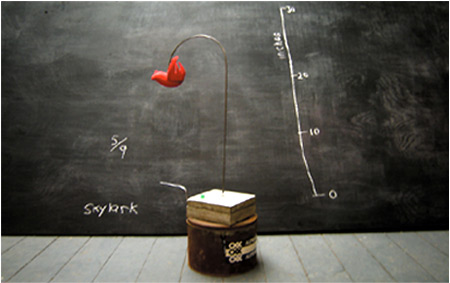

Lisa Malone

Metronome |

|||

|

||||

|

||||

|

Metronome Lisa Malone Lisa Malone, an artist working at Flaxart studios, Belfast, presents Metronome, an exhibition exploring and experimenting with her practice. It features a suite of new sculptural interventions, as well as a series of monoprints. Malone�s work is a playful comment on human nature, suggestive rather than literal, and allows a multitude of readings. Thursday 14th January from 6pm � 8pm The exhibition runs until 30th January 2010. Art Projects @ London Art Fair 13-17 January 2010 Curated by Sarah McAvera, the Belfast-based Golden Thread Gallery presents an exhibition which attempts to investigate the relevance of "Troubles" artwork produced during, or inspired by, the 30-year period of turbulent conflict in Northern Ireland. Looking at the artwork, which often shows a world in stark contrast to today's era of peace and rebuilding, the issue of its relevancy arises. Is it detrimental to the local mentality to display and therefore continuously re-examine and discuss the "Troubles", or can it be used as a way of archiving the experience and thus moving forward? Does Troubles-inspired artwork overshadow all art produced in Northern Ireland, or does it provide a context to better understand this difficult and contentious era of contemporary history? A questioning and scepticism of community, representation, religion and death pervade the artwork in this exhibition, which includes artwork in various media by some of Northern Ireland's leading visual artists. Victor Sloan's photography projects a tense locality where a newly constructed town, intended to be a neutral space, seethes with a precarious, sinister atmosphere. Continuing on the idea of two opposing bodies, Ian Charlesworth's work highlights the tension between the two segregated but parallel communities, by exploring the physical gesture in graffiti. The subjective nature of representation is challenged in Graham Gingles' stencilled images of army men and crowds, which evoke a film negative and the ease in which it can be edited: made negative or positive, cropped, reduced or 'blown up'. Strategic juxtapositions of religious iconography alongside heavy artillery create a deadly association in Marie Barrett's landscapes, and religious imagery is utilised again in Gerry Gleason's paintings, which recall medieval icons while exploring lost freedoms and the weight of tradition. Death and violence feature heavily in Troubles artwork, and Tom Bevan defies the violence with his bright, cheerfully painted wooden guns, turning these symbols of death and destruction into harmless objects of beauty. Philip Napier's sculpture of a funeral wreath commemorates the dead in a sombre gesture, while on the other hand Peter Richards's work, created post-Good Friday agreement, questions memory and memorial and brings us back to the initial question of the exhibit: what is the relevance of Troubles artwork in a stable, prosperous era? Elizabeth Bell, writer, Chigago |

||||

re-title.com

International contemporary art

SIGN UP FOR NEWSLETTERS

SIGN UP for ARTIST MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for GALLERY MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for ARTIST MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for GALLERY MEMBERSHIP

Click on the map to search the directory