|

David Kordansky Gallery: ZACH HARRIS - Echo Parked in a No Vex Cave || GRAPEVINE~ - 29 June 2013 to 17 Aug 2013 Current Exhibition |

||||

|

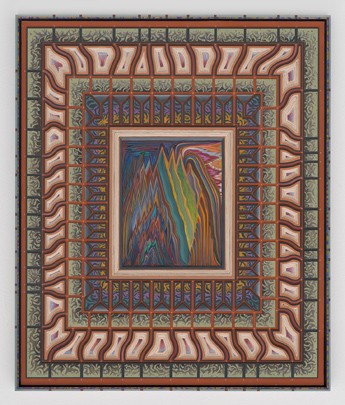

Zach Harris, G's Early Work, 2011-2013

water based paint, wood 30 x 25 inches (76.2 x 63.5 cm) |

|||

|

||||

|

Zach Harris Echo Parked in a No Vex Cave June 29 – August 17, 2013 Opening reception: Saturday, June 29, 6:00–9:00pm David Kordansky Gallery is very pleased to announce Echo Parked in a No Vex Cave, an exhibition of new paintings by Zach Harris. The show will run from June 29 until August 17, 2013; an opening reception will be held on Saturday, June 29, from 6:00 until 9:00pm. This is the artist's first exhibition at the gallery. Zach Harris makes objects that fall generally under the rubric of painting but that defy any attempt at easy categorization. Neither wholly representation nor wholly abstract, each work is resolved through a combination of technique, craft, and honing of vision. Furthermore, Harris pursues an idiosyncratic and highly personal vocabulary that paradoxically allows him to engage with an array of sources drawn from numerous cultural and natural contexts. In art historical terms, these include predecessors as diverse as the holy architectural and geometrical visions of the pre-Renaissance Sienese; the optical complexity and patterning conjured by Tibetan mandala-makers; and the interior/exterior vistas and landscapes of Americans like Charles Burchfield and Forrest Bess. In some cases these traditions reflect alternatives to the mainstream or deviations from the majority of contemporary painting practice. More importantly, however, they all emphasize that form is not merely an abstract visual language, but rather a connection between the physical world and the otherworldly realms that surround it and course through its center. Perhaps for this reason, viewers new to Harris' paintings are often most immediately struck by the intricacy of their construction. Frames, which are an integral part of each composition, are carved, built, routed and painted, and are sculptural works in and of themselves. The paintings at their centers, meanwhile, are worked with a level of detail, representation and spatial illusion that only reveals its full extent after long periods of viewing. In Harris' case, physicality is a reflection of time: the physical frame functions as a way to prolong and intensify the viewing experience, creating puzzling shifts in consciousness as the eye is hypnotically coaxed toward a singular source of focus. In this sense too his process must be described as a traditional one, not because of its historicity, but because it eschews the rapid glance in favor of meditative, fully embodied looking. Several of the paintings in Echo Parked in a No Vex Cave are the artist's largest to date. The increased scale allows Harris to further extend and define the peripheral field in order to engage the viewer's body as well as the eye. It also provides additional potential for experimentation with both 2-D and 3-D forms. Broad painterly gestures bring attention to flat surfaces while simultaneously alluding to deeper illusionistic spaces and calibrated color fields. The intimacy of the relationship between eye, hand, and object that is so condensed in the smaller works therefore expands to suggest resonances between the painting and the entire body. That the level of detail remains constant regardless of scale is only further testament to Harris' commitment to developing entire worlds of hue, form, and image; indeed, the paintings are like ecosystems that evolve according to their own laws of natural selection. Distinctions between center and periphery are therefore revealed to be no more than distinctions of perspective. In some works the figure (i.e. the painting) and its surrounding environment (the frame) enter into symbiotic concert. In others, like Belvedere Torso/Finger Scales, it is the figure that defines the overall experience of seeing, relegating ideas of containment to the perceptual edge. But it is also important to note those instances in which apparent differences between two phases (frame/painting, image/sculpture, landscape/abstraction) of the same painting are resolved by a third, namely the conscious and unconscious energies of the observer. It is this third phase in which the ecstatic brand of formalism that unites diverse artifacts of all kinds, from all phases of history and positions inside of and outside of the canon, finds its purest expression: a shared space in which artist and viewer perform analogous––if not identical––roles as instigators of order and enlightened witnesses of chaos. Zach Harris (b. 1976, Santa Rosa, CA) was included in Made in L.A. 2012 at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. His work has been featured and reviewed in Artforum, The New York Times, Modern Painters, and is in the permanent collections of the Hammer Museum; the Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ; and the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, CA. Harris lives and works in Los Angeles. GRAPEVINE~ Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, Michael Frimkess, John Mason, Ron Nagle, Peter Shire curated by Ricky Swallow July 13 – August 17, 2013 Opening reception: Saturday, July 13, 6:00–9:00pm GRAPEVINE~ was conceived as way of exhibiting a group of artists who have all worked in clay, in California, for more than 40 years. Throughout that time these artists have always sought to contradict the limitations of the medium in terms of its craft parameters. It might sound obvious, but there is something about this work brewing on the West Coast. I can't imagine it surfacing anywhere else with its strangeness paired with such dedication to finish and quality. The show is intended to reflect a fan's perspective rather than an exhaustive attempt to chronicle the history of the ceramics movement in California, as the Pacific Standard Time exhibitions recently performed this function perfectly. It's revealing to consider the works on view in light of the current state of ceramics in the contemporary art world. Though clay is drawing new attention among younger artists, these "visitors," as one ceramics elder described them to me, seem to be focused on bringing out the medium's malleable qualities. Meanwhile the "permanent residents" are very much still exceeding themselves in the studio. The specific agendas put forward by publications like Craft Horizons in the 1960s and 70s, calling for the promotion of new directions in ceramics, could today seem like a fence, limiting any cross-pollination between craft and contemporary practices. The work in GRAPEVINE~, much of it created during the extended "lost weekend" the medium experienced over the previous decades, resonates more than ever right now as a retroactive influence. Historically the very nature of the ceramic medium implies the tradition of setting up a studio (or pottery), building the appropriate kilns, and constantly performing glaze and clay body tests in order to attain the desired effect. To me, this romantic (some might say dated) discipline is the thing that separates the work of the permanent residents from that of the visitors. For instance, John Mason still mixes his own clay body in an archaic industrial bread mixer, and Michael Frimkess develops latex gloves with stainless steel fingernails in order to throw his large vessels (without the aid of water) to the desired thinness. This rigor results in specific families of forms that can be identified throughout each artist's body of work––in many cases recurring motifs span decades of object-making––and a sense of serious play is always checked by technical discipline. Perhaps even more surprising is the range of cultural information that makes appearances in so many different ways: I'm thinking about how art deco, custom car culture and architecture informs Peter Shire and Ron Nagle's work; or how popular staples of American comic imagery adorn the classically-inflected pots of Michael and Magdalena Suarez Frimkess; or the way Mason's work has such a Jet Propulsion Laboratory-engineered vibe. The more familiar gestural "abstract expressionist" style of the 50s and 60s, which for many defines ceramics-based work from California, is only a small part of the story. In subsequent decades these artists found their own specific languages, a natural evolution as the medium was applied toward more purely sculptural ends. At the same time, they were crossing paths in studios and universities, influencing each other and the course of the ceramics movement at large. For instance, Nagle was in San Francisco paying close attention to the gang surrounding Peter Voulkos (who is represented in the exhibition by a small work gifted to Mason during their time as studio mates); this gang eventually became the group of ceramicists associated with Ferus Gallery here in Los Angeles, though I was surprised to learn how influential Michael Frimkess's early works were for Nagle at the time. Revered by other artists working with clay, Frimkess never received the same ongoing exposure as Ken Price, Billy Al Bengston and Mason, who were his peers studying under Voulkos in the mid 1950s at the Los Angeles County Art Institute (later Otis College of Art and Design). Magdalena Suarez Frimkess, meanwhile, came from a sculpture background, studied in Chile, and never trained formally as a potter. She began by working collaboratively, glazing Michael's pots from the time they met in the early 60s in New York, before starting to make her own sculptures and hand-formed pots in 1970. Arriving a few thousand years after the Greek and Chinese vessels they resemble, and a few decades before the pictorial pots of Grayson Perry, these objects occupy a place between many genres and continue a rich tradition of narrative storytelling through pottery. Shire, some years younger than the others in the show, was also a keen observer, later becoming friends with Nagle and Mason––it was Peter who first introduced me to John. Interestingly, there was already an existing connection between Shire and Frimkess, as their fathers were acquainted through labor unions in Los Angles in the 1940s and 50s, and both artists were raised in creative households infused with progressive politics, modernism, and craftsmanship. And one can perhaps trace connections between Shire's Memphis-associated work and the moment when Nagle's earliest, more malleable cup variations gave way to a pre-Memphis form of architecture. More recently Nagle's work has featured stucco-like, spongy, ikebana-core tableaux, and archimetric structures made with a model maker's precision; parts are shaped, adjusted and fitted together, and glazed with multiple firings to wizardly effect. The fastidious steps behind all of the works in GRAPEVINE~ remain available to the viewer as tight information, yet always with enough variation and nuance to locate them within the studio environment as opposed to more familiar traits of outsourced fabrication. The formal training of a potter (a skill which is now weeded out of the few ceramics programs still in place) is visible in all of this work: proportion, the lift provided by a well-trimmed foot, and the energy and circulation of the clay itself are still defining factors. For the most part all included works have come directly from the artists, and I am grateful to have been allowed such a degree of physical searching and selecting during studio visits. The privilege of this access has both shaped the show in a very tactile and subjective manner, and allowed a greater understanding of the historic, technical, and conceptual conditions that inform each piece. In addition to the artists, I would like to thank Ryan Conder, Karin Gulbran, Vernita Mason, Pam Palmer, Lesley Vance, and David Kordansky. For further information, a comprehensive interview with each of the artists in the show can be found archived online in the Smithsonian Archives of American Art: http://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/ ––Ricky Swallow GRAPEVINE~ will be accompanied by a forthcoming catalogue. Please contact the gallery for further details. |

||||

|

||||

re-title.com

International contemporary art

SIGN UP FOR NEWSLETTERS

SIGN UP for ARTIST MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for GALLERY MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for ARTIST MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for GALLERY MEMBERSHIP

Click on the map to search the directory