|

CUE Art Foundation: Raul Guerrero - Curated By Allen Ruppersberg Carrie Olson - Curated By Natalie Marsh - 21 Jan 2010 to 13 Mar 2010 Current Exhibition |

||||

|

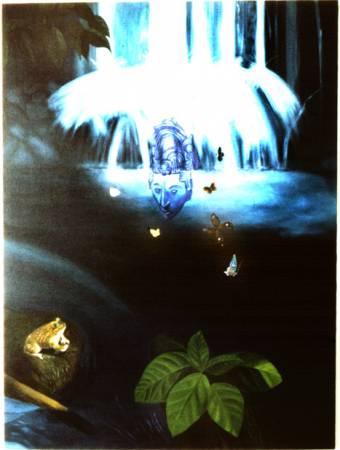

Raul Guerrero, The Pool of Palenque, 1985

Oil on canvas, 60� x 44� Courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Ollman |

|||

|

||||

|

||||

|

Raul Guerrero Curated By Allen Ruppersberg Carrie Olson Curated By Natalie Marsh January 21 - March 13, 2010 Raul Guerrero Curated by Allen Ruppersberg Artist's Statement Oaxaca, Mexico Summer, 1965 I'm 19 years old, a college dropout hitchhiking around Mexico and for some reason have ended up in Oaxaca. The Zocalo is surrounded by huge trees and has a bandstand serving as the center of gravity for the evening promenade, a mass of people circling people. Some in this throng are well dressed others not, some wear shined shoes, huaraches or simply go barefoot, hats no hats, clipped hair long hair, on and on. Kids run around chasing each other. Zapotec and Mixtec women wear gold and silver, selling trinkets and copper copies of jewelry discovered in ancient burial chambers. All the while la banda plays, waltzes, danzones or revolutionary period marching tunes. Summer, 1968 My art school girlfriend and I are hitchhiking Mexico and stop in Oaxaca. From our pension we can hear someone playing an ancient sound on a flute, a tune echoing the images we encountered that day in the ancient city of Monte Alb�n. Later in the Zocalo we sit on a bench observing the evening events. A man sitting next to us strikes up a conversation and after awhile asks if we would like to have lunch with him and his family. We accept the invitation. The next day we find ourselves in a remote village and eventually locate the adobe house. It has a corrugated tin roof and the dirt floor interior is recently swept and newly sprinkled with water. We have a simple lunch, and then taking me aside asks if we would please take his eldest daughter to the United States. He says poverty is making life difficult and he would like to give her to us. Autumn, 1984 The bus from Teococuilco comes by at 8:10 AM, on its way to Oaxaca and the market. I get up and prepare for the trip into town to buy painting supplies. I make coffee, shower, dress, and open the bathroom windows overlooking the waterfall and stream running underneath the building. Formerly a wheat mill, it's now my painting studio and home for the next six months. The studio offers a panoramic view of the valley below, the sun is reflecting off of slow moving clouds, and the distant mountains are obscured by a light rain. The bus finally arrives. It looks circa 1947, is painted bright yellow with blue trim, worn tires are covered in mud and the name El Llanero Solitario (The Lone Ranger) is written in Old English script on the side. The bus door opens to the blare of Mexican music. I step up and make eye contact with as many people as possible, and offer a greeting. A few respond, most are asleep as they have been on the road since early morning. The passengers are mostly children, and shawl wrapped women with bundles of goods, they are strongly indigenous looking, probably Zapotec. Curator's Statement by Allen Ruppersberg When I decided to nominate Raul Guerrero for a slot on CUE Art Foundation's exhibition program, I suggested showing his series of paintings begun in 1984 in Oaxaca, Mexico, because I had never quite forgotten them. They were his first foray into painting and have remained unique - at least to me - throughout his subsequent career, which has mostly focused on painting, and in particular, painting a sense of place. This series had never, to my knowledge been shown together, but had been painted as a group and in a consistent and original style. That style might be defined as primitive but not na�ve, with a touch of magic realism from the time and incorporating a narrative feeling of space coming from his sculptural tableaus of the past. The elements that made the sculptural environments stand out had passed into the paintings. His current work has grown into something more sophisticated or knowledgeable most would say, myself included, but I am also still thoroughly attracted to those first efforts. I selfishly wanted to see them all together at least one time. I first met Raul at the Chouinard Art Institute where we were both students in the mid 1960's. It was a decade later, however, when we coincidently found ourselves living in the same apartment building in Santa Monica, that we became close friends and that I began to know more completely his work and ideas. Raul's art at the time was a formally mixed approach of the interdisciplinary kind characteristic of this period. Centering primarily on sculpture, it included film, video, photography, found and appropriated objects often placed in a kind of tableau, drawing, and prints. There was a specific, conceptualized slant to these combinations that was familiar to me, beginning with a sort of Duchampian Dada and incorporating strains of surrealism, outr� (at the time) painters like Raul Dufy, kitsch illustration, and the general detritus of Spanish and American cultural history that he found growing up in the San Diego area of Southern California. Then in 1984, as he has told me, he tired of trying to infuse these by then mostly straight ahead sculptural projects with the emotional world he was living in. He decided to try to render this world in paint rather than objects and chose as his first subject the Mexican city of Oaxaca. This was to initiate an interest in painting cities and a certain range of subjects that continue to occupy him to this day. I think of this early effort in Oaxaca as the touchstone of what was to come later and what was to embody, for him, some of the best thoughts in a new/old medium. Carrie Olson Curated by Natalie Marsh Artist's Statement I am interested in the role objects play in our lives - the status we assign them and what that communicates about our identity, be it personal or societal. While this is an ongoing theme in my work, over the past few years I have also been quite focused on fear - what provokes it, how we process it and how it can be manipulated. It seems this past decade has been defined by a carefully choreographed dance dominated by consumption and fear; a dance in which the majority of the population participates. The work in this exhibition centers on porcelain respirators that I have cast from molds of half-face respirators. Their material (Limog�s porcelain) speaks of ornament, collectability and status, but their form implies a very specific utility. These respirators act as a vehicle for exploring how changes in cultural context make an object more valuable. The run on duct tape and respirators after 9-11 and the ubiquitous sight of dust masks in Hong Kong and Toronto during the SARS scare and once again this year with the swine flu, are recent examples of how quickly an object's value can shift in the culture. Surrounding these respirators is a "spectacle" comprised of large digital prints and hand carved porcelain disks. The images on the disks and prints are created from microscopic photographs of virulent organisms that I digitally replicate, alter and arrange into patterns. The disks are round like a Petri dish and many of the patterns are inspired by Busby Berkeley's choreography. These types of elaborate dance routines were very tightly choreographed to create purely ornamental human formations, where the individual is important only as a component of the composition. I exploit the role of ornament as mediator; it is the system through which the content of the work is both constructed and filtered. Specifically, I draw on the transformative nature of ornament as a device to examine the complexities of identity construction in contemporary culture. Curator's Statement by Natalie Marsh In 1982, Thomas McEvilley wrote of the hold that Clement Greenberg's formalism exerted on the discourse of 20th century art: "Passionate belief systems pass through cultures like disease epidemics." McEvilley's declaration raises intriguing concerns when considering the most recent work of ceramicist Carrie Olson. Situated in the simultaneously epistemologically delicate yet powerfully subtle sites between Greenbergian distinctions of pure form and illustrative content, potentially neither, potentially either, productively both, ornament may be located along a visually and conceptually sweeping continuum. Carrie Olson's patterned multi-media installations insist at first that we allow ourselves to be absorbed by her insidiously alluring "flora" ornamentations but then "dis-ease" sets in when we find Olson assigns signification-motivating diagnostic titles, Marburg Galliard, H5N1 Cakewalk, the double evocations of disease and folk dance. Her digitally manipulated wallpapers illustrate, in the arbitrary representational sense, the forms of myriad microscopic microbes and viruses. She surrounds us with their vibrant and somehow comforting repeating structure. Yet, disorientation is articulated through the wallpaper's literal shortfall; it does not reach the floor and hangs like a dubious standard. Floating like treasured porcelain heirloom plates atop these "banners" are low relief disks disguising their dangerous petri-dish inhabitants who dance harmless "waltzes." These "follies," as Olson aptly describes them, suggest the nature of parallel cultural constructions: fear and the soothing market-ready domestic arsenal to conceal and control it. The continuum along which Olson's works travel is twisted and turned upon itself, like a Mobius strip upon which form and content exert inseparable and indistinguishable identities. This challenges Greenberg, who asserted, "The avant-garde poet or artist sought to maintain a high level of his art by both narrowing and raising it to the expressions of an absolute...�Art for art's sake' and �pure poetry' appeared, and subject matter or content became something to be avoided like the plague." Olson's work is an ironic redrawing of Greenberg's autonomous art; it literally represents disease and plague embodied in exquisite form. Her content is her form. Olson's work thus also grapples with the overarching concerns of late 20th century ceramic art discourse that have both polarized and ghettoized ceramics and ceramic artists for decades: does form trump function, and does art trump craft? Olson cleverly bypasses this discourse in the intimately interconnected content and form of her imagery of the paradoxes of contemporary life. Olson does not deal in absolutes; her work is deeply imbricated with layers of manipulated and intertwining meanings, with both formal and conceptual implications, that reflect 21st century existence. Wryly, she asks us to passionately breathe through the false logic of insufficient cotton masks, and reminds us that propaganda still works even if we know its languages. |

||||

re-title.com

International contemporary art

SIGN UP FOR NEWSLETTERS

SIGN UP for ARTIST MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for GALLERY MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for ARTIST MEMBERSHIP

SIGN UP for GALLERY MEMBERSHIP

Click on the map to search the directory